“Bonds as an asset class will always be needed, and not just by insurance companies and pension funds, but by aging boomers.” – Bill Gross, Janus Capital

We have had many client conversations about interest rates, bond returns, and the merits of fixed income.

Admittedly, 2018 has been a tough year for bond investors as short-term and (finally) long-term yields have drifted higher. The anxiety amongst bond investors has been amplified by the relatively strong performance of the U.S. equity market. No one likes to own “boring” bonds while their neighbor boasts about their appreciating Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google positions.

The Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (blue) is down ~2.16% year-to-date (as of 10/16/2018). For context, the S&P 500 is up ~6.56% year-to-date.

Given that bonds are a cornerstone piece for many retirees for both risk reduction and income, we wondered the last time U.S. fixed income posted back to back negative return years?

To keep things clean, we focus on recent history (1987-2018), nominal (before inflation) returns, and the U.S. bond market.

First for some context:

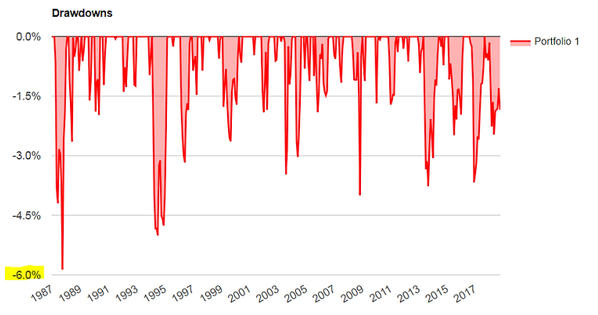

Source: Portfoliosvisualizer.com

The above graphic shows drawdowns for the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index since 1987. This isn’t a realized loss, but rather a measure of downward movement. Generally, the steeper the drawdown, the more volatile an asset.

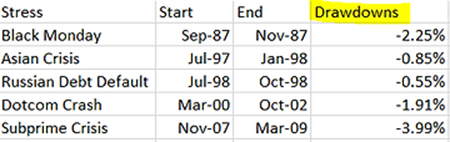

Source: PortfolioVisualizer.com

The above chart shows market stress events since 1987 and the corresponding U.S. bond drawdowns.

Despite a crisis every decade or so for the past 30 years, bond returns proved resilient.

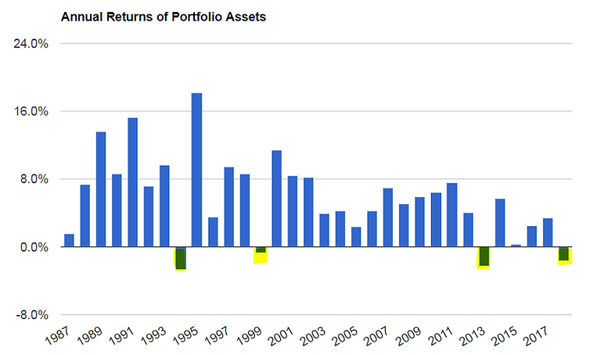

The above graph shows annual returns for U.S. bonds by year. Amazingly, over the last 30 years, bonds have not posted back to back negative return years.

We concede the backdrop of our sample size was pure heaven for a bond investor i.e. falling interest rates and tame inflation.

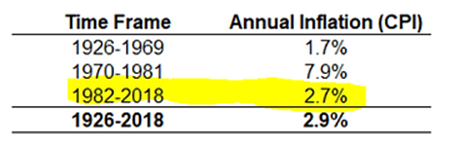

Source: A Wealth of Common Sense Blog

The above chart shows a modest and stable level of inflation over the past 30+ years.

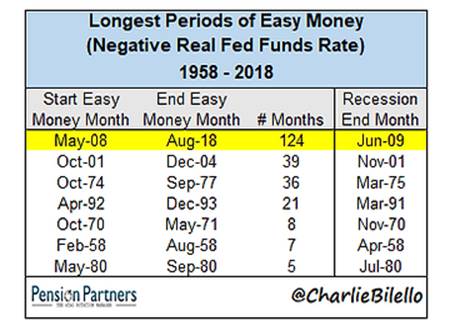

The backdrop is turning less accommodative as monetary policy shifts from easy to normalized (more restrictive than in past years).

The real Fed funds rate is now positive for the first time since the mid 2000s. In other words, interest rates are higher than core inflation. This is considered more restrictive monetary policy.

Recent history suggests bond returns are relatively stable (admittedly aided by favorable low inflation and falling interest rates). However, what’s true today might not be so in the future. Unexpected inflation and wavering confidence of the full, faith, and credit of United States government could change the narrative around the U.S. bond market.

For now, the U.S. was named by the World Economic Forum as the most competitive country in the world (first time since 2008) for our “innovative ecosystem.” Our place as the world’s reserve currency means stability and a safe-haven for global capital. A mature economy typically doesn’t get outlandish bouts of inflation. There’s no doubt the next 30 years will present new challenges for U.S. bond investors, but empirical evidence and economic climate suggests bonds will do their job to mitigate risk and provide income for investors.