“Our discussions of the economy may sometimes ring in the ears of the public with more certainty than is appropriate.” Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve Chairman

There’s been much hand-wringing over when the Fed is going to start tapering. We define tapering as the Fed reducing bond purchases.

The Fed purchases bonds, also called quantitative easing, to keep long-term interest rates low.

Low interest rates incentivizes businesses to borrow money for new projects, capital expenditures, hire workers, expand operations, etc.

Households and individuals are more likely to borrow money to buy a home, remodel, buy a boat or car, when money is cheap.

The debate amongst investors is, when the Fed is going to taper and how does it affect market volatility & stock prices?

Tapering too quickly as economic growth slows could derail a fragile recovery.

Tapering too slowly could fuel higher inflation, asset bubbles, and promote excessive risk-taking.

Historically, the Fed monitors inflation and employment data to make monetary policy decisions. This is a very difficult task under normal circumstances. It’s a crapshoot during a global pandemic.

Whether stocks move up or down shouldn’t concern the Fed, but it’s undeniable that Fed policy is impacted by the risk appetite of investors (look no further than Q4 2018, more on that below).

Investors can use recent history to understand how the mechanics of a taper might look. We evaluate how U.S. stock prices behaved prior, during, and upon completion of the previous taper cycle…

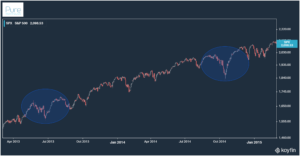

June 2013, Bernanke announces the Fed will reduce asset purchases.

Over the course of the next ~15 months, the Fed incrementally decreased the dollar amount of bonds purchased.

October 2014, the Fed was no longer purchasing bonds. The taper cycle was complete.

Source: Koyfin

The above chart shows the S&P 500’s performance when the Fed announced the taper (first blue circle) June 2013. The second blue circle shows the completion of Fed bond purchases in October 2014. There was noise pre-taper and upon completion, but nothing out of the ordinary in-between.

A couple observations…

- The Fed reducing bond purchases doesn’t mean the end of accommodative monetary policy. It simply means less aggressive accommodation.

- Policy changes, like whether to reduce, increase, or stop bond purchases, aren’t set it stone. The Fed can change course depending on economic data trends and market dynamics. Furthermore, the reduction of bond purchases will happen gradually over a period of time (the last taper cycle lasted ~15 months).

- The Fed will not raise interest rates until they stop buying bonds.

- In the previous tapering cycle, stocks behaved erratically when the Fed changed course. We define changing course as a shift in monetary policy. For example, going from buying bonds to tapering, tapering to not buying bonds, and not buying bonds to rate increases.

The communication between the Fed and market participants (investors) is key. Market volatility can occur when market expectations are out of lock-step with Fed action. Look no further than the 4th quarter of 2018. The market threw a fit and the Fed quickly reversed course…

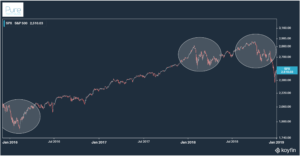

Source: Koyfin

The above chart shows S&P 500 returns from 12/2015 to 12/2018. During that period, the Fed increased interest rates nine times. Based on the market volatility (latter two circles), investors thought it was one or two hikes too many. Responding to the tantrum thrown by investors, the Fed would go on to reverse course and begin cutting rates in 2019. Ironically, the period was dubbed “the taper tantrum.”

While the last taper cycle provides context, there is no guarantee the next taper cycle will look the same. However, there is evidence to suggest volatility clusters around monetary policy.

Don’t fall for the narrative central bankers are in control. Predicting inflation, employment, and investor risk appetites is damn near impossible. The Fed is a reactionary follower of economic data and market dynamics.

The Fed is one variable in a complex system. There are millions of other variables that influence stock prices and investor risk appetites.

For more on Fed policy and markets, see “Not Buying what the Fed is Selling.“