“You can take advantage of pockets of opportunity in what people don’t want.” – Jeff Gundlach, DoubleLine CEO

We’ve been fielding a decent number of municipal bond inquiries lately. Normally a boring asset class, there have been a number of developments over the past couple months that: a) changed the way we are getting exposure, and, b) have provided attractive opportunities if you know where to look.

For those who don’t follow fixed income markets, a municipal bond is a debt security issued by a state, municipality or county to finance its capital expenditures, including the construction of highways, bridges or schools. They can be thought of as loans that investors make to local governments. Municipal bonds are exempt from federal taxes and most state and local taxes, making them especially attractive to people in high income tax brackets (source, Investopedia).

A popular mental short-cut to measure the attractiveness of municipal bonds is the muni to treasury ratio. In short, the ratio measures current municipal bond yields vs. U.S. Treasuries. For example, a AAA rated muni yielding 1% vs. a U.S. 10-year yielding 1.5% would result in a ratio of 1%/1.5% = 0.66. The higher the ratio, the more attractive municipal bonds are relative to Treasuries. This ratio is often less than 1 (meaning munis yield less than Treasuries) because of favorable tax treatment of municipal bond interest payments.

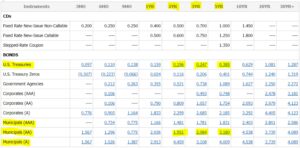

Here is what the current set-up looks like…

Source: Charles Schwab

The above graphic shows the yield to maturity (YTM) for several bond sub-categories (as of 5/4/20). Notice the difference in YTM for 1 to 5 year maturity Treasuries vs. AA/AAA municipal bonds. The muni to Treasury ratio is off the charts! Could this be a field day for the savvy muni investor?

There’s no free lunch in investing. The higher yields in muni bonds are an indicator of potential trouble. Many states faced budget shortfalls and huge unfunded pension obligations before COVID-19. The budget problems of states are likely to get worse and the outsized yields reflect that, however, there are pockets of value and not all municipal bonds are the same. Look no further than the crazy swings in municipal bond ETFs during the middle of March…

Source: Ycharts

The above chart shows the dramatic drawdown of two municipal bond ETFs. Despite owning bonds of the highest credit rating, AA/AAA exclusively, the funds were behaving more like equities. We have always preferred individual bonds, but these dramatic moves confirmed our resolve.

The Fed recently launched the municipal liquidity facility, which states the Fed can directly buy up to $500 billion in municipal bonds from states, cities with more than one million people, and counties with more than two million people. Unfortunately, that still leaves a huge potential funding gap for smaller municipalities that do not meet the above criteria.

The savvy municipal bond investor can earn a much higher after-tax yield compared to Treasuries. We should note that individual bond investing can be intimidating, even for financial advisors. Fixed income is one of the most confusing and complex asset classes out there.

Here is rough outline for purchasing individual municipal bonds:

- We try and target individual bonds with maturities ranging from one to seven years. This is especially important if you’re dabbling in speculative issues (lower rated bonds). Would you rather lend a shaky borrower money for 18 months or eight years?

- Individual bonds should be held until maturity. The only way to suffer a capital loss on an individual issue is to sell prior to maturity or if the borrower defaults.

- If you’re buying individual bonds and hold them until maturity, you can satellite bond ETFs for liquidity purposes. For example, if you take a monthly distribution you can easily sell the ETFs to satisfy liquidity needs. You can also use ETFs to tactically get exposure to longer dated maturities which tend to hold up well during economic shocks.

- You should buy individual bonds in minimum $50,000 lots. The pricing and available inventory is much better than buying smaller lots. There are exceptions, but generally this is a good rule to follow.

- Target municipal bonds from places people want to live, large population tax bases, good schools, stable local governments, attractive to big business, moderate climate.

- Headline risk can create value. For example, Washington State fits the above criteria (desirable place to live, etc.), but was at the epicenter of COVID-19. We’ve been picking up solid bonds as investors outside of the region dump WA bonds without fully understanding the local dynamics.

- We prefer revenue bonds which are backed by a specific institution, essential service (water/sewer) or project. We are interested in bonds that have the political capital for support if things go poorly. Think hospitals, school districts, mass transit, and public universities.

- Avoid bonds in rural states or areas, beware of general obligation bonds for states with large budget deficits or unfunded pensions (Illinois), avoid states that are politically dysfunctional (this is becoming more difficult with each passing year).

Municipal bond investors should use common sense. There are exceptions, but these are good rules to follow especially if you’re just getting started.

Note: General obligation bonds (GO) are backed by the credit and taxing power of the entire jurisdiction rather than a specific project.