“The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” John Maynard Keynes, Economist

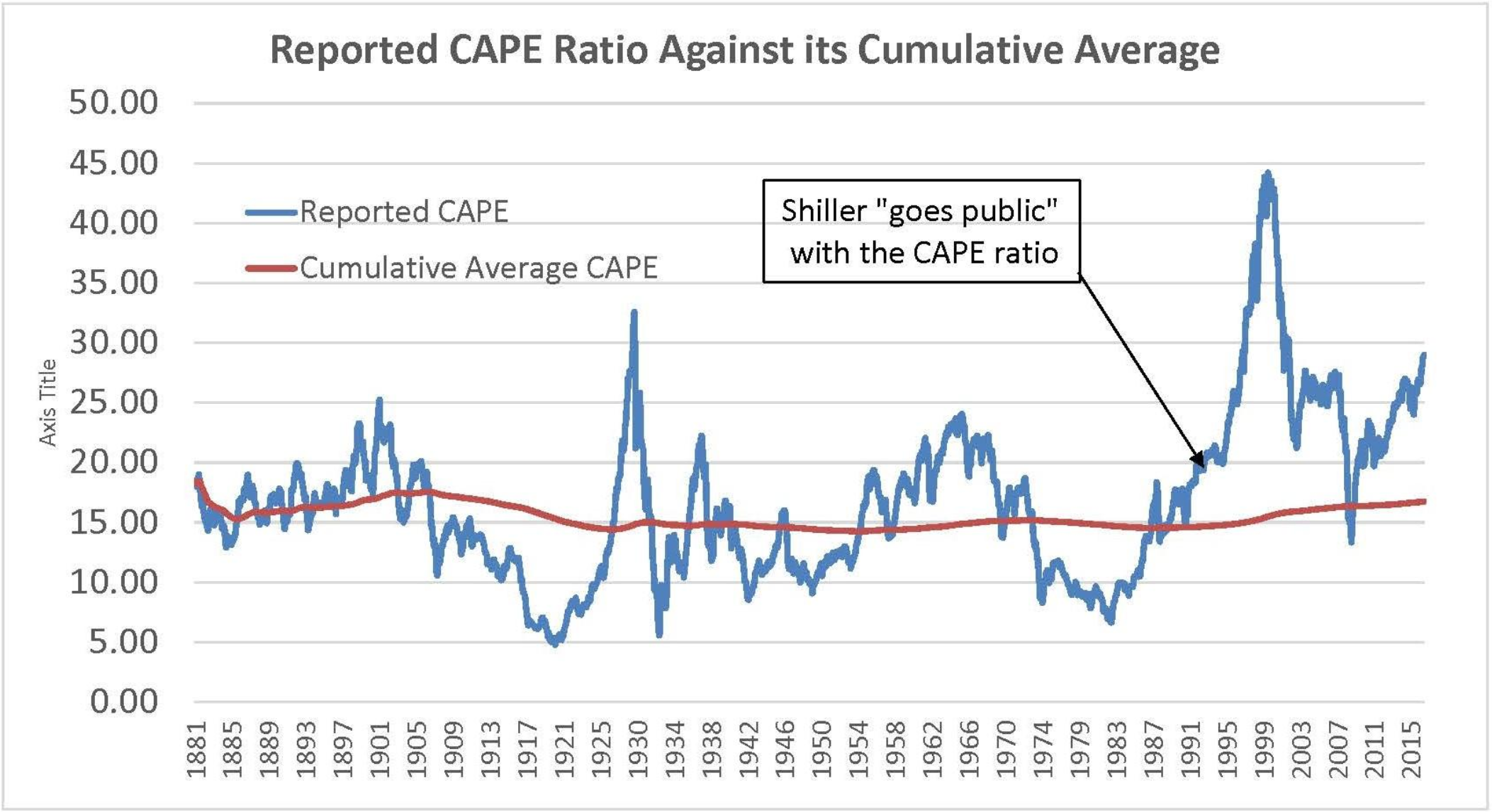

The Shiller price to earnings ratio (CAPE) is a popular metric to measure stock market valuation. It’s easy to both understand and apply to individual stocks or broader market indices. It’s currently flashing warning signals that the market is grossly overvalued. The problem is the alarm has been sounding for the better part of three decades (aside from a brief stretch during the financial crisis of 2008-2009).

Shiller P/E ratio definition: The ratio is a valuation measure, generally applied to broad equity indices, that uses real per-share earnings over a 10-year period. The P/E 10 ratio uses smoothed real earnings to eliminate the fluctuations in net income caused by variations in profit margins over a typical business cycle (read more here). Source: Investopedia.

Source: Investopedia.

The red line indicates the mean or average CAPE. The CAPE ratio hovers around a level of 16 dating back to 1881. At face value, we can say anytime the blue line is above the red line, the market is overvalued. Conversely, when the blue line is below the red line, the market is undervalued. I’m interested in the period from 1988+.

Observations:

- Extreme levels of valuation, either down (1920s) or up (1999), can offer insight on future returns. A general rule is low valuation indicates higher future returns, while higher valuation levels often indicate lower future returns. Note: this doesn’t say anything about the timing of those future returns. This is an important distinction.

- If you made investment decisions based solely on valuation, you would have likely missed out on outsized returns from 2011 – 2017.

- Low interest rates and low inflation support higher equity valuations. Investors have been forced to take risk to generate a real (after inflation) return as it has been challenging to generate a meaningful return in safe investments i.e. cash.

- There is a behavioral human component to the equation. This has been the most unloved bull market run in modern history. In our opinion, investors are still sensitive to the scars of 2008 and it’s made them hyper-sensitive to potential losses.

Ben Carlson, of Wealth of Common Sense Blog, has some additional thoughts on what would signal excessive market valuation:

(1) Everyone around you talking about stocks (or real estate or whatever the fad asset of the day is). And you should really start worrying when the people talking about getting rich in certain areas of the market don’t have a background in finance.

(2) When people begin quitting their jobs to day trade or become a mortgage broker.

(3) When someone exhibits skepticism about the prospects for stocks and people don’t just disagree with them, but they do so vehemently and tell them they’re an idiot for not understanding things.

(4) When you start to see extreme predictions. The example Bernstein gives is how the best-selling investment book in 1999 was Dow 36,000.

As strong as one’s belief that the market is overvalued, making investment decisions strictly on valuation has often produced sub-optimal results.